A brief political history of the paisley

Plus Val Kilmer and George Foreman

A couple of weeks ago I went to an interesting lecture about the history of the paisley pattern and paisley shawls, at, of all places, the Bank of England Museum.

The lecture was inspired by the 1859 painting “Dividend Day at the Bank of England” by English Victorian painter George Elgar Hicks. The painting, which is owned by the museum, depicts the once-a-quarter day during which dividends from Consolidated Government Annuities were paid to applicants. These “consols”, as they were known, were the only investments available to widows and orphans, according to the National Trust. This gave Hicks the opportunity to depict several women in his painting in an environment that would otherwise be dominated by men.

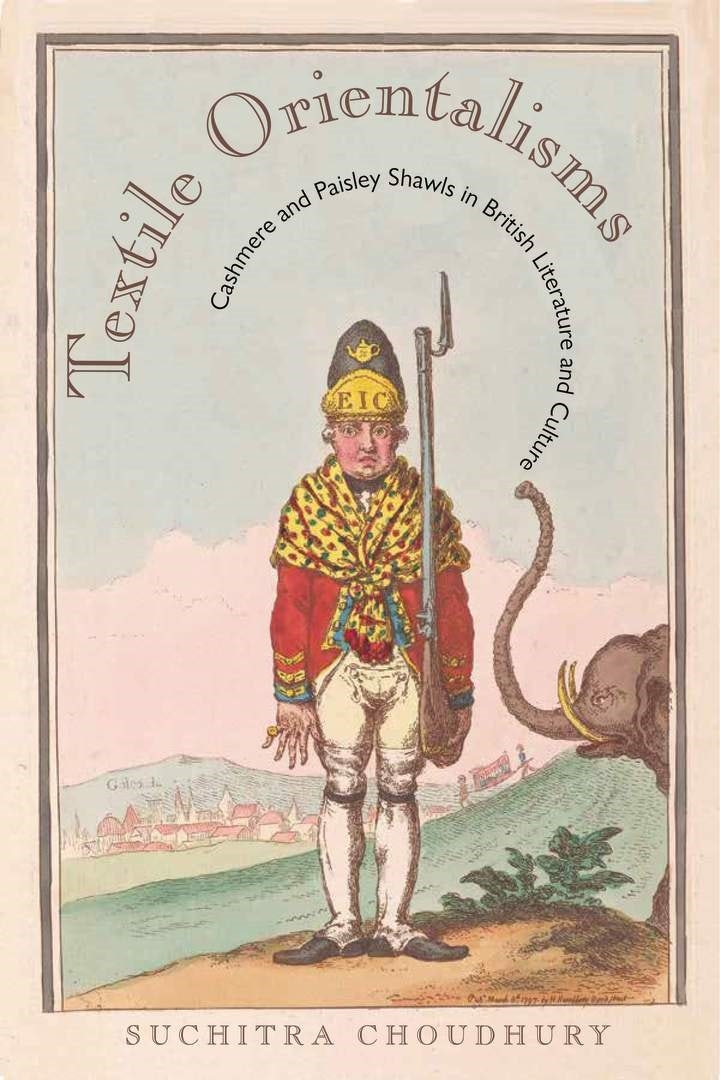

In the center left of the painting, partially obscured by other characters, is a young woman in a vivid sky blue and pink shawl which appears to be decorated with paisley patterns. Dr. Suchitra Choudhury, a research affiliate at the University of Glasgow who is an expert in the history of Indian textiles and their interplay in British culutre, used the character in the painting as a jumping off point to discuss the meaning of the paisley.

Such shawls were considered the “Gucci and YSL of their time,” during the Raj, Choudhury explained. Historically, in India, fine shawls made from the wool of either Kashmir goats or chiru antelope were often given as high-status gifts, usually to men. During the mid 1800s, these shawls were transported back to England where, much like high-fashion brands of today, they were frequently copied for the middle and lower classes. Whereas a true Indian shawl might be made out of fine goat hair, a British knockoff would be made of a less-expensive material that was readily available in the UK — sheeps wool.

Also in India, shawls would be decorated with specific weave patterns and motifs indicative of their regions of origin (hence the term “cashmere shawl”). One of those motifs, the buta, was known in English as the pinecone or teardrop design. When commercial wool weavers in Paisley, Scotland, began making knock-off shawls featuring this pattern, it became known by its new name, the paisley.

Being a powerful symbol of India, the shawl soon became more than just a garment. Choudhury notes that the paisley shawl was used as a symbolic reference in political cartoons and other media, such as Wilkie Collins’ novel Armadale. Collins’ character Lydia, who wears a red paisley shawl, which “reflected and generated the memory of the Indian rebellion (of 1857) via the shawl's links with India, and Collins employs it as a narrative strategy to raise a sense of terror and uncertainty,” Choudhury writes. Collins was already outspoken in his compassion for India, she argues, and thus the shawl became “an indirect reference to the plight of the Indian rebel whose claims for justice were largely unheard.”

As Choudhury was speaking I was thinking of the parallels between the 18th century shawl and a more modern symbol of resistance, the keffiyah, which has been both vilified and comodified throughout history. At one point in the Oughts even Urban Outfitters was selling a version, similar to the paisley knockoffs in Victorian England.

The paisley pattern came back into vogue in the 1960s, this time without the political underpinnings, thanks to fashion designer Emilio Pucci, who is widely considered to have popularized the pattern. Choudhury told me she suspects the resurgence of the pattern had more to do with the exoticism and interest in Eastern philosophy that permeated the 1960s than anything else.

Remnants of the paisley shawl craze also popped up in the late 1990s, when a generation of Western moms because obsessed with pashmina scarves, typically made from a combination of cashmere and silk. Trickles of this trend resurged again with the quiet luxury movement popularized by Tiktok.

At any rate, the history of the paisley shawl is long and fascinating, spanning countries and even political movements in a time before we though of trends as going “viral.” Now, every time I see a man wearing a paisley necktie, I’ll think of “Dividend Day at the Bank of England”, Wilkie Collins, the Indian Rebellion, and the ingenuity of fiber artists everywhere.

Documentaries, now

I can't even think of a pithy way to headline this section, as Val Kilmer was one of my all-time favorite actors, and I wasn't even old enough to fall in love with him in Weird Science or Top Gun. My favorite movie of his is of course Tombstone, but a close second is the maligned and unhinged 1996 remake of Island of Dr. Moreau, during which he worked with his mentor a moribund Marlon Brando.

This incredibly campy scene from Tombstone alone is worth the price of admission (also featuring another favorite, Michael Biehn — god everyone is in this movie). It's one of those films that is required watching if you ever run across it on late night cable or while staying in a hotel or on an airplane.

If you haven't seen the 2021 documentary Kilmer made about his life, Val, it is also required viewing. It certainly changed my perspective on his enfent terrible Hollywood reputation. His Mark Twain project looked incredible and I am sad to have not seen it.

Also last month, boxer and Houstonian George Foreman died. Here is where I recommend that you watch When We Were Kings, the incredible documenatry about "the rumble in the jungle", the boxing match between Foreman and Muhammed Ali staged by Don King in Zaire in 1974. This isn't much of a spoiler but does not come off very well in this film (or in the match). Not only is this one of the greatest sports documentaries of all time, it's probably one of the best documentaries full-stop that I've ever seen. And I'm not even a boxing fan.

Important stuff

- "So, my life and plans have changed quite dramatically over the last few months." Cartoonist R.E. Burke is documenting her 19-day ICE detainment on Instagram and in a future book.

- "“I think that these people deserve the dignity of at least someone paying attention to what’s happening to them." The Retired J.P. Morgan Executive Tracking Trump’s Deportation Flights

- London police arrested six people at Quaker Meeting House discussion of climate change and Gaza last week. “No-one has been arrested in a Quaker meeting house in living memory,” said Paul Parker, recording clerk for Quakers in Britain, according to the statement. In case you don't know, Quakers espouse nonviolence, , prison abolition, don't believe in war, are anti-slavery, and do not have hierarchal structures in their denominations. More on the arrests here.

- And taking another page from US policy, Berlin seeks to deport EU citizens over pro-Palestinian protests.

- Footage of Gaza, like this and this, makes me want to scream, cry and throw up.

- United States Disappeared Tracker

That’s all for today. I love you, thanks for reading. If you liked this email please share it with a friend.